His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso

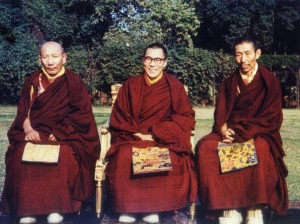

His Holiness with His Senior Tutor, the 6th Kyabje Yongzin Ling Rinpoche (left) and His Junior Tutor, the 3rd Kyabje Trijang Rinpoche (right) 1956

A Brief Biography

His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, is both the head of state and the spiritual leader of Tibet. He was born on 6 July 1935, to a farming family, in a small hamlet located in Taktser, Amdo, northeastern Tibet. At the age of two the child, who was named Lhamo Dhondup at that time, was recognized as the reincarnation of the 13th Dalai Lama, Thubten Gyatso. The Dalai Lamas are believed to be manifestations of Avalokiteshvara or Chenrezig, the Bodhisattva of Compassion and patron saint of Tibet. Bodhisattvas are enlightened beings who have postponed their own nirvana and chosen to take rebirth in order to serve humanity.

Education in Tibet

His Holiness began his monastic education at the age of six. The curriculum consisted of five major and five minor subjects. The major subjects were logic, Tibetan art and culture, Sanskrit, medicine, and Buddhist philosophy which was further divided into five categories: Prajnaparimita, the perfection of wisdom; Madhyamika, the philosophy of the Middle Way; Vinaya, the canon of monastic discipline; Abidharma, metaphysics; and Pramana, logic and epistemology. The five minor subjects were poetry, music and drama, astrology, metre and phrasing, and synonyms.

At 23 he sat for his final examination in the Jokhang Temple, Lhasa, during the annual Monlam (prayer) Festival in 1959. He passed with honours and was awarded the Geshe Lharampa degree, the highest-level degree equivalent to a doctorate of Buddhist philosophy.

Leadership Responsibilities

In 1950 His Holiness was called upon to assume full political power after China’s invasion of Tibet in 1949. In 1954, he went to Beijing for peace talks with Mao Zedong and other Chinese leaders, including Deng Xiaoping and Chou Enlai. But finally, in 1959, with the brutal suppression of the Tibetan national uprising in Lhasa by Chinese troops, His Holiness was forced to escape into exile. Since then he has been living in Dharamsala, northern India, the seat of the Tibetan political administration in exile.

Since the Chinese invasion, His Holiness has appealed to the United Nations on the question of Tibet. The General Assembly adopted three resolutions on Tibet in 1959, 1961 and 1965.

Democratisation Process

In 1963 His Holiness presented a draft democratic constitution for Tibet that was followed by a number of reforms to democratise the administrative set-up. The new democratic constitution promulgated as a result of this reform was named “The Charter of Tibetans in Exile”. The charter enshrines freedom of speech, belief, assembly and movement. It also provides detailed guidelines on the functioning of the Tibetan government with respect to those living in exile.

In 1992 His Holiness issued guidelines for the constitution of a future, free Tibet. He announced that when Tibet becomes free the immediate task would be to set up an interim government whose first responsibility will be to elect a constitutional assembly to frame and adopt Tibet’s democratic constitution. On that day His Holiness would transfer all his historical and political authority to the Interim President and live as an ordinary citizen. His Holiness also stated that he hoped that Tibet, comprising of the three traditional provinces of U-Tsang, Amdo and Kham, would be federal and democratic.

In May 1990, the reforms called for by His Holiness saw the realisation of a truly democratic administration in exile for the Tibetan community. The Tibetan Cabinet (Kashag), which till then had been appointed by His Holiness, was dissolved along with the Tenth Assembly of Tibetan People’s Deputies (Tibetan parliament in exile). In the same year, exile Tibetans on the Indian sub-continent and in more than 33 other countries elected 46 members to the expanded Eleventh Tibetan Assembly on a one-person one-vote basis. The Assembly, in its turn, elected the new members of the cabinet. In September 2001, a further major step in democratisation was taken when the Tibetan electorate directly elected the Kalon Tripa, the senior-most minister of the Cabinet. The Kalon Tripa in turn appointed his own cabinet who had to be approved by the Tibetan Assembly. In Tibet’s long history, this was the first time that the people elected the political leadership of Tibet.

Peace Initiatives

In September 1987 His Holiness proposed the Five Point Peace Plan for Tibet as the first step towards a peaceful solution to the worsening situation in Tibet. He envisaged that Tibet would become a sanctuary; a zone of peace at the heart of Asia, where all sentient beings can exist in harmony and the delicate environment can be preserved. China has so far failed to respond positively to the various peace proposals put forward by His Holiness.

The Five Point Peace Plan

In his address to members of the United States Congress in Washington, D.C. on 21 September 1987, His Holiness proposed the following peace plan, which contains five basic components:

- Transformation of the whole of Tibet into a zone of peace.

- Abandonment of China’s population transfer policy that threatens the very existence of the Tibetans as a people.

- Respect for the Tibetan people’s fundamental human rights and democratic freedoms.

- Restoration and protection of Tibet’s natural environment and the abandonment of China’s use of Tibet for the production of nuclear weapons and dumping of nuclear waste.

- Commencement of earnest negotiations on the future status of Tibet and of relations between the Tibetan and Chinese peoples.

Strasbourg Proposal

In his address to members of the European Parliament in Strasbourg on 15 June 1988, His Holiness made another detailed proposal elaborating on the last point of the Five Point Peace Plan. He proposed talks between the Chinese and Tibetans leading to a self-governing democratic political entity for all three provinces of Tibet. This entity would be in association with the People’s Republic of China and the Chinese Government would continue to remain responsible for Tibet’s foreign policy and defence.

Universal Recognition

His Holiness the Dalai Lama is a man of peace. In 1989 he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his non-violent struggle for the liberation of Tibet. He has consistently advocated policies of non-violence, even in the face of extreme aggression. He also became the first Nobel Laureate to be recognized for his concern for global environmental problems.

His Holiness has travelled to more than 62 countries spanning 6 continents. He has met with presidents, prime ministers and crowned rulers of major nations. He has held dialogues with the heads of different religions and many well-known scientists.

Since 1959 His Holiness has received over 84 awards, honorary doctorates, prizes, etc., in recognition of his message of peace, non-violence, inter-religious understanding, universal responsibility and compassion. His Holiness has also authored more than 72 books.

His Holiness describes himself as a simple Buddhist monk.

A More Detailed Biography of His Holiness the Dalai Lama

Birth

His Holiness the Dalai Lama was born on 6 July 1935, and named Lhamo Thondup, to a poor family in the small village of Taktser in the province of Amdo. The name, Lhamo Thondup, literally means Wish-Fulfilling Goddess. Taktser (Roaring Tiger) was a small and poor settlement that stood on a hill overlooking a broad valley. Its pastures had not been settled or farmed for long, only grazed by nomads. The reason for this was the unpredictability of the weather in that area, His Holiness writes in his autobiography Freedom in Exile. During my early childhood, my family was one of twenty or so making a precarious living from the land there.

His Holiness’ parents were small farmers who mostly grew barley, buckwheat and potatoes. His father was a man of medium height with a very quick temper. I remember pulling at his moustache once and being hit hard for my trouble, recalls His Holiness. Yet he was a kind man too and he never bore grudges. His Holiness recalls his mother as undoubtedly one of the kindest people I have ever known. She had a total of sixteen children, of whom seven lived.

His Holiness had two sisters and four brothers who survived their infancy. Tsering Dolma, the eldest child, was eighteen years older than His Holiness. At the time of my birth she helped my mother run the house and acted as my midwife. When she delivered me, she noticed that one of my eyes was not properly open. Without hesitation she put her thumb on the reluctant lid and forced it wide fortunately without any ill effect, His Holiness writes. His Holiness’ three elder brothers were Thupten Jigme Norbu – the eldest, who was recognised as the reincarnation of a high lama, Taktser Rinpoche – Gyalo Thondup and Lobsang Samten. The youngest brother, Tenzin Cheogyal was also recognised as the reincarnation of another high lama, Ngari Rinpoche.

Of course, no one had any idea that I might be anything other than an ordinary baby. It was almost unthinkable that more than one tulku (reincarnation) could be born into the same family and certainly my parents had no idea that I would be proclaimed Dalai Lama, His Holiness writes. Though the remarkable recovery made by His Holiness’ father from his critical illness at the time of His Holiness’ birth was auspicious, it was not taken to be of great significance. I myself likewise had no particular intimation of what lay ahead. My earliest memories are very ordinary. His Holiness recollects his earliest memory, among others, of observing a group of children fighting and running to join in with the weaker side.

One thing that I remember enjoying particularly as a very young boy was going into the chicken coop to collect the eggs with my mother and then staying behind. I liked to sit in the hens’ nest and make clucking noises. Another favourite occupation of mine as an infant was to pack things in a bag as if I was about to go on a long journey. I’m going to Lhasa, I’m going to Lhasa, I would say. This, coupled with my insistence that I be allowed always to sit at the head of the table, was later said to be an indication that I must have known that I was destined for greater things.

His Holiness is held to be the reincarnation of each of the previous thirteen Dalai Lamas of Tibet (the first having been born in 1391 AD), who are in turn considered to be manifestations of Avalokiteshvara, or Chenrezig, Bodhisattva of Compassion, holder of the White Lotus. Thus His Holiness is also believed to be a manifestation of Chenrezig, in fact the seventy-fourth in a lineage that can be traced back to a Brahmin boy who lived in the time of Buddha Shakyamuni. I am often asked whether I truly believe this. The answer is not simple to give. But as a fifty-six year old, when I consider my experience during this present life, and given my Buddhist beliefs, I have no difficulty accepting that I am spiritually connected both to the thirteen previous Dalai Lamas, to Chenrezig and to the Buddha himself.

Discovery as Dalai Lama

When Lhamo Thondup was barely three years old, a search party that had been sent out by the Tibetan government to find the new incarnation of the Dalai Lama arrived at Kumbum monastery. It had been led there by a number of signs. One of these concerned the embalmed body of his predecessor, Thupten Gyatso, the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, who had died aged fifty-seven in 1933. During its period of sitting in state, the head was discovered to have turned from facing south to northeast. Shortly after that the Regent, himself a senior lama, had a vision. Looking into the waters of the sacred lake, Lhamo Lhatso, in southern Tibet, he clearly saw the Tibetan letters Ah, Ka and Ma float into view. These were followed by the image of a three-storied monastery with a turquoise and gold roof and a path running from it to a hill. Finally, he saw a small house with strangely shaped guttering. He was sure that the letter Ah referred to Amdo, the northeastern province, so it was there that the search party was sent.

By the time they reached Kumbum, the members of the search party felt that they were on the right track. It seemed likely that if the letter Ah referred to Amdo, then Ka must indicate the monastery at Kumbum, which was indeed three-storied and turquoise-roofed. They now only needed to locate a hill and a house with peculiar guttering. So they began to search the neighbouring villages. When they saw the gnarled branches of juniper wood on the roof of the His Holiness’ parent’s house, they were certain that the new Dalai Lama would not be far away. Nevertheless, rather than reveal the purpose of their visit, the group asked only to stay the night. The leader of the party, Kewtsang Rinpoche, then pretended to be a servant and spent much of the evening observing and playing with the youngest child in the house.

The child recognised him and called out ‘Sera lama, Sera lama’. Sera was Kewtsang Rinpoche’s monastery. The next day they left only to return a few days later as a formal deputation. This time they brought with them a number of things that had belonged to the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, together with several similar items that did not. In every case, the infant correctly identified those belonging to the Thirteenth Dalai Lama saying, It’s mine. It’s mine. This more or less convinced the search party that they had found the new incarnation. It was not long before the boy from Taktser was acknowledged to be the new Dalai Lama. The boy Lhamo Thondup was first taken to Kumbum monastery. There now began a somewhat unhappy period of my life, His Holiness was to write later, reflecting on his separation from his parents and the unfamiliar surroundings. However, there were two consolations to life at the monastery. First, His Holiness’ immediate elder brother Lobsang Samten was already there. The second consolation was the fact that his teacher was a very kind old monk, who often held his young disciple inside his gown.

Lhamo Thondup was eventually to be reunited with his parents and together they were to journey to Lhasa. This did not come about for some eighteen months, however, because Ma Bufeng, the local Chinese Muslim warlord, refused to let the boy-incarnate be taken to Lhasa without payment of a large ransom. It was not until the summer of 1939 that he left for the capital, Lhasa, in a large party consisting of his parents, his brother Lobsang Samten, members of the search party and other pilgrims.

The journey to Lhasa took three months. I remember very little detail apart from a great sense of wonder at everything I saw: the vast herds of drong (wild yaks) ranging across the plains, the smaller groups of kyang (wild asses) and occasionally a shimmer of gowa and nawa, small deer which were so light and fast they might have been ghosts. I also loved the huge flocks of hooting geese we saw from time to time.

Lhamo Thondup’s party was received by a group of senior government officials and escorted to Doeguthang plain, two miles outside the gates of the capital. The next day, a ceremony was held in which Lhamo Thondup was conferred the spiritual leadership of his people. Following this, he was taken off with Lobsang Samten to the Norbulingka, the summer palace of His Holiness, which lay just to the west of Lhasa.

During the winter of 1940, Lhamo Thondup was taken to the Potala Palace, where he was officially installed as the spiritual leader of Tibet. Soon after, the newly recognised Dalai Lama was taken to Jokhang temple where His Holiness was inducted as a novice monk in a ceremony known as taphue, meaning cutting of the hair. From now on, I was to be shaven-headed and attired in maroon monk’s robes. In accordance with ancient custom, His Holiness forfeited his name Lhamo Thondup and assumed his new name, Jamphel Ngawang Lobsang Yeshe Tenzin Gyatso.

His Holiness then began to receive his primary education. The curriculum – same as that for all monks pursuing a doctorate in Buddhist studies – included logic, Tibetan art and culture, Sanskrit, medicine and Buddhist philosophy. The last and the most important (and most difficult) was subdivided into further five categories: Prajnaparamita, the perfection of wisdom; Madhyamika, the philosophy of the Middle Way; Vinaya, the canon of monastic discipline; Abidharma, metaphysics; and Pramana, logic and epistemology.

Dalai Lama in His Youth

On the day before the opera festival in the summer of 1950, His Holiness was just coming out of the bathroom at the Norbulingka when he felt the earth beneath begin to move. As the scale of this natural phenomenon began to sink in, people naturally began to say that this was more than a simple earthquake: it was an omen.

Two days later, Regent Tathag received a telegram from the Governor of Kham, based in Chamdo, reporting a raid on a Tibetan post by Chinese soldiers. Already the previous autumn there had been cross-border incursions by Chinese Communists, who stated their intention of liberating Tibet from the hands of imperialist aggressors. It now looked as if the Chinese were making good their threat. If that were so, I was well aware that Tibet was in grave danger for our army mustered no more than 8,500 officers and men. It would be no match for the recently victorious People’s Liberation Army (PLA).

Two months later, in October, news reached Lhasa that an army of 80,000 soldiers of the PLA had crossed the Drichu river east of Chamdo. So the axe had fallen. And soon, Lhasa must fall. As the winter drew on and the news got worse, people began to advocate that His Holiness be given his majority, his full temporal power. The Government consulted the Nechung Oracle, a very tense moment, who came over to where His Holiness was seated and laid a kata, a white offering scarf, on His Holiness’s lap with the words ‘Thu-la bap’, His time has come. At the young age of fifteen, His Holiness was on 17 November 1950 officially enthroned as the temporal leader of Tibet in a ceremony held at the Norbulingka Palace.

At the beginning of November, about a fortnight before the day of His Holiness’s investiture, his eldest brother arrived in Lhasa. As soon as I set eyes on him, I knew that he had suffered greatly. Because Amdo, the province where we were both born, and in which Kumbum is situated, lies so close to China, it had quickly fallen under control of the Communists. He himself was kept virtual prisoner in his monastery. At the same time, the Chinese endeavoured to indoctrinate him in the new Communist way of thinking and try to subvert him. They had a plan whereby they would set him free to go to Lhasa if he would undertake to persuade me to accept Chinese rule. If I resisted, he was to kill me. They would then reward him.

To mark the occasion of his ascension to power, His Holiness granted general amnesty whereby all the prisoners were set free. I was pleased to have this opportunity, although there were times that I regretted it. When I trained my telescope on the compound, it was empty save for a few dogs scavenging for scraps. It was as if something was missing from my life.

Shortly after the 15-year-old Dalai Lama found himself the undisputed leader of six million people facing the threat of a full-scale war, His Holiness appointed two new Prime Ministers. Lobsang Tashi became the monk Prime Minister and an experienced lay administrator, Lukhangwa, the lay Prime Minister.

That done, I decided in consultation with them and the Kashag to send delegations abroad to America, Great Britain and Nepal in the hope of persuading these countries to intervene on our behalf. Another was to go to China in the hope of negotiating a withdrawal. These missions left towards the end of the year. Shortly afterwards, with the Chinese consolidating their forces in the east, we decided that I should move to southern Tibet with the most senior members of the Government. That way, if the situation deteriorated, I could easily seek exile across the border with India. Meanwhile, Lobsang Tashi and Lunkhangwa were to remain in an acting capacity.

While His Holiness was in Dromo, which lay just inside the border with Sikkim, His Holiness received the news that while the delegation to China had reached its destination, each of the others had been turned back. So it was almost impossible to believe that the British Government was now agreeing that China had some claim to authority over Tibet. His Holiness was equally saddened by America’s reluctance to help. I remember feeling great sorrow when I realised what this really meant: Tibet must expect to face the entire might of Communist China alone.

Frustrated by the indifference showed to Tibet’s case by Great Britain and America, His Holiness, in his last bid to avoid a full-scale Chinese invasion, sent Ngabo Ngawang Jigme, governor of Kham, to Beijing to open a dialogue with the Chinese. The delegation hadn’t been given the power to reach at any settlement, apart from its entrusted task of convincing the Chinese leadership against invading Tibet. However, one evening, as I sat alone A harsh, crackling voice announced that a Seventeen-Point ‘Agreement’ for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet had that day (May 23, 1951) been signed by representatives of the Government of the People’s Republic of China and what they called the Local Government of Tibet. As it turned out, the Chinese who even forged the Tibetan seal had forced the delegation headed by Ngabo into signing the agreement. The Chinese had in effect secured a major coup by winning Tibetan compliance, albeit at gunpoint, to their terms of returning Tibet to the fold of the motherland. His Holiness returned to Lhasa in the middle of August 1951

Countdown to Escape

The next nine years saw His Holiness trying to evade a full-scale military takeover of Tibet by China on one hand and placating the growing resentment among Tibetan resistance fighters against the Chinese aggressors on the other. His Holiness made a historic visit to China from July 1954 to June 1955 for peace talks and met with Mao Zadong and other Chinese leaders, including Chou En-lai, Chu Teh and Deng Xiaoping. From November 1956 to March 1957 His Holiness visited India to participate in the 2500th Buddha Jayanti celebrations. But disheartening reports of increasing brutality towards his own people continued to pour in when the young Dalai Lama was giving his final monastic examinations in Lhasa in the winter of 1958/59.

Escape into Exile

One winter day of 1959 (March 10) General Chiang Chin-wu of Communist China extended a seemingly innocent invitation to the Tibetan leader to attend a theatrical show by a Chinese dance troupe. When the invitation was repeated with new conditions that no Tibetan soldiers was to accompany the Dalai Lama and that his bodyguards be unarmed, an acute anxiety befell the Lhasa populace. Soon a crowd of tens of thousands of Tibetans gathered around the Norbulingka Palace, determined to thwart any threat to their young leader’s life.

On 17 March 1959 during a consultation with Nechung Oracle, His Holiness was given an explicit instruction to leave the country. The Oracle’s decision was further confirmed when a divinity performed by His Holiness produced the same answer, even though the odds against making a successful break seemed terrifyingly high.

A few minutes before ten o’clock His Holiness, now disguised as a common soldier, slipped past the massive throng of people along with a small escort and proceeded towards Kyichu river, where He was joined by the rest of the entourage, including his immediate family members.

In Exile

Three weeks after leaving Lhasa, His Holiness and his entourage reached the Indian border from where they were escorted by Indian guards to Bomdila. The Indian government had already agreed to provide asylum to His Holiness and his followers in India. It was in Mussoorie that His Holiness met with the Indian Prime Minister and the two talked about rehabilitating the Tibetan refugees.

Realising the importance of modern education for the children of Tibetan refugees, His Holiness impressed upon Nehru to undertake the formation of an independent Society for Tibetan Education within the Indian Ministry of Education. The Indian Government was to bear all the expenses for setting up the schools for the Tibetan children.

Thinking the time is ripe for me to break my elected silence’, His Holiness called a press conference on 20 June 1959 when His Holiness formally repudiated the Seventeen-Point Agreement. In the field of administration, too, I was able to make radical changes. For example, His Holiness saw the creation of various new Tibetan government departments. These included Departments of Information, Education, Home, Security, Religious Affairs and Economic Affairs. Most of the Tibetan refugees, whose number had grown to almost 30,000, were moved to road camps in the hills of northern India.

On 10 March 1960 just before leaving for Dharamsala with the eighty or so officials who comprised the Tibetan Government-in-Exile, His Holiness began what is now a tradition by making a statement on the anniversary of the Tibetan People’s Uprising. On this first occasion, I stressed the need for my people to take a long-term view of the situation in Tibet. For those of us in exile, I said that our priority must be resettlement and the continuity of our cultural traditions. As to the future, I stated my belief that, with Truth, Justice and Courage as our weapons, we Tibetans would eventually prevail in regaining freedom for Tibet.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama

Three Main Commitments

His Holiness has three main commitments in life.

Firstly, on the level of a human being, His Holiness’ first commitment is the promotion of human values such as compassion, forgiveness, tolerance, contentment and self discipline. All human beings are the same. We all want happiness and do not want suffering. Even people who do not believe in religion recognize the importance of these human values in making their life happier. His Holiness refers to these human values as secular ethics. He remains committed to talk about the importance of these human values and share them with everyone he meets.

Secondly, on the level of a religious practitioner, His Holiness’ second commitment is the promotion of religious harmony and understanding among the world’s major religious traditions. Despite philosophical differences, all major world religions have the same potential to create good human beings. It is therefore important for all religious traditions to respect one another and recognize the value of each other’s respective traditions. As far as one truth, one religion is concerned, this is relevant on an individual level. However, for the community at large, several truths, several religions are necessary.

Thirdly, His Holiness is a Tibetan and carries the name of the ‘Dalai Lama’. Tibetans place their trust in him. Therefore, his third commitment is to the Tibetan issue. His Holiness’ has a responsibility to act as the free spokesperson of the Tibetans in their struggle for justice. As far as this third commitment is concerned, it will cease to exist once a mutually beneficial solution is reached between the Tibetans and Chinese.

However, His Holiness will carry on with the first two commitments till his last breath.

A Routine Day of His Holiness the Dalai Lama

When asked by people how His Holiness the Dalai Lama sees himself, he replies that he is a simple Buddhist monk. Even in his daily life, His Holiness remarks that he spends 80% of his time on spiritual activities and the other 20% on Tibet.

His Holiness is often out of Dharamsala on travels both within India and abroad. During these travels, His Holiness’s daily routine varies depending on his engagement schedule. However, His Holiness is an early riser and tries as far as possible to retire early in the evening.

When His Holiness is at home in Dharamsala, he wakes up at 3.30 a.m. After his morning shower, His Holiness begins the day with prayers, meditations and prostrations until 5.00 a.m. From 5.00 a.m. His Holiness takes a short morning walk around the residential premises. If it is raining outside, His Holiness has a treadmill to use for his walk. Breakfast is served at 5.30 a.m. For breakfast, His Holiness typically has hot porridge, tsampa (barley powder), bread with preserves, and tea. Regularly during breakfast, His Holiness tunes his radio to the BBC World News in English. From 6 a.m. to 8.30 a.m. His Holiness continues his morning meditation and prayers. From around 9.00 a.m. until 11.30 a.m. he studies various Buddhist texts written by the great Buddhist masters. Lunch is served from 11.30 a.m. until 12.30 p.m. His Holiness’s kitchen in Dharamsala is vegetarian. However, during visits outside of Dharamsala, His Holiness is not necessarily vegetarian. As an ordained Buddhist monk, His Holiness does not have dinner. Should there be a need to discuss some work with his staff or hold some audiences and interviews, His Holiness will visit his office from 12.30 p.m. until around 4.30 p.m. Typically, during an afternoon at the office one interview is scheduled along with several audiences, both Tibetan and non-Tibetan. Upon his return to his residence, His Holiness has evening tea at 6 p.m. He then has time for his evening prayers and meditation from 6.30 p.m. until 8.30 p.m. Finally, after a long 17-hour day His Holiness retires for bed at 8.30 p.m.

Travels by His Holiness the Dalai Lama

His Holiness the Dalai Lama made his first foreign visit outside Tibet in 1954 when he spent almost a year in China meeting with its leaders and touring various places. In 1956, His Holiness made his second visit abroad to India at the invitation of the Mahabodhi Society of India to attend the 2500th Birth Anniversary Celebrations of Lord Buddha. In 1959, His Holiness once again returned to India, this time as a refugee escaping the brutal Chinese occupation of Tibet, thus beginning his life in exile.

With the initial years of exile being focused on the rehabilitation of tens of thousands of Tibetan refugees in India, His Holiness made many visits within India visiting the refugees and their newly established camps. In 1967, His Holiness made his first visits abroad since coming into exile, visiting Japan and Thailand. In 1973, His Holiness made his first visit to the West, visiting 12 European countries in a record 75 days! His first visit to the Americas was to the United States and Canada in 1979.

The above information is reprinted from various pages within www.dalailama.com/the-dalai-lama. See that link for more information, including a timeline of His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s life events, and lists of His awards/honours received, dignitaries met, books published and places visited.

For more information about the previous thirteen H.H. the Dalai Lamas, click here.